This newsletter is a reader-supported publication. We’re trying to keep things as free as possible, but if you enjoy what I write and want access to exclusive weekly recipes, and if you are at a point in your life to support our newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

Yesterday I was in Bologna to attend XFood, an event by Soluzione Group in collaboration with Scuola Holden. The theme of the event was the storytelling of food as seen from new points of view, and along with other professionals we tackled the topic of food storytelling, each with his or her own perspective. I talked about recipes, their power, their value. The following is the talk I gave yesterday, I hope you will realize how fascinating, profound, and complex is the world of recipe writing.

I am a home cook who develops recipes, but I am also someone who cooks a lot of recipes written by other cooks.

So I know that there is nothing more disappointing than a recipe that doesn't work. When we test a recipe, write it down, and then put it out there in the world, someone will find it: it may be the readers of our newsletter, someone who buys our cookbooks, someone who follows our profiles on social media, or someone who stumbles across our blog searching for Tuscan fried chicken, or eggplant parmigiana, or savoy cabbage soup.

If those people pick our recipe, it means that they are investing time and money in us, they are investing their trust. The least we can do is make ourselves worthy of their trust and recognize the value of that investment of time and money.

And how can we do that? The first step is not to underestimate the power and the complex world hidden behind a recipe. A recipe is a blend of poetry, science, and political activism.

A recipe is poetry.

A recipe, just like a poem, should create as vivid an image as possible in the reader's mind. You find yourself sitting on the couch, a cookbook in your hand. You begin to read a recipe, and slowly you get an idea of the process, of the feelings you will have rolling out the risen dough on a wooden surface, of the end result. Even of the smell that will waft from the oven once the focaccia is baked. You will precisely perceive, in your mind, on your tongue, and on your taste buds, the grains of coarse sea salt, the puddles of briny olive oil, the crisp surface, and the soft, yielding crumb.

The next step is to get up and go to the kitchen to check if you still have enough flour for the focaccia. This is one of the characteristics that a good recipe has in common with poetry: it creates imaginary worlds that seem real, and it awakens memories and feelings.

With poetry, recipe writing shares the use of rhetorical figures that help make the language more vivid and effective. Similes and metaphors serve precisely this function.

Nigel Slater, in his The Christmas Chronicles, writes, speaking of panforte:

“There is also something ancient about this shallow, fudge-coloured sweetmeat. As if you were chewing a medieval manuscript.”

As an almost Sienese person, I have never found a more effective description, one that succeeds in bringing together the texture, history, and tradition of panforte.

Besides this, recipe writing benefits from a strong, active, specific language, just as in poetry. We should be parsimonious with adjectives—less is more—, and favour active verbs and specific nouns. So not pasta, but spaghetti. Not good, delicious, yummy, but sugary, creamy, comforting, crunchy, moist, punchy, aromatic, you name it.

If writing recipes is like writing poetry, we can finally legitimize that food writing— and recipe writing!—is not a minor genre; food writing is literature.

[I know this has been amply recognized in Anglo-American literature, but it is not in Italy, and it is worth re-asserting at any given chance).

Speaking of the importance of language and adjectives when we write about food, let me quote a very romantic movie from the 1990s, City of Angels. Meg Ryan is a surgeon in Los Angeles. Nicolas Cage is an incorporeal angel who falls in love with her. I don't want to spoil the ending in case you haven't seen this romantic drama, I will just quote this dialogue between the two lovers.

Seth: What’s that like? What’s it taste like? Describe it like Hemingway.

Maggie: Well, it tastes like a pear. You don’t know what a pear tastes like?

Seth: I don’t know what a pear tastes like to you.

Maggie: Sweet, juicy, soft on your tongue, grainy like a sugary sand that dissolves in your mouth. How’s that?

Seth: It’s perfect.

A recipe is science.

A recipe is like a mathematical formula, there are precise ingredients and quantities, chemical reactions happening in the kitchen, acids and bases, fats and heat. Just like in a scientific experiment, precision is needed when we are in the kitchen testing a recipe. Among my favourite tools when I develop a recipe there is a ruler, to measure the size of pots and pans, a stopwatch—hey Alexa, set a 15-minute timer, onions—and a notebook, where I write down all the steps, times, and, most importantly, visual references.

In fact, to write a recipe that works, it is not enough to say: bake the cake for 45 minutes because we all know that every oven is different, that temperatures vary, as do environmental conditions. So I'll have to say: bake the cake for 45 minutes, or until… a toothpick inserted in the centre comes out clean, or the edges are golden brown, and the centre is still slightly wobbly, or until—and I'm thinking about a fruit pie—the syrup starts to simmer on the edges.

We have a perfect example in Italy of a cookbook author who writes recipes with a scientific approach. I’m thinking about Dario Bressanini and his books, such as La Scienza della Pasticceria, La Scienza della Carne, and La Scienza delle Verdure, and the detailed, precise, scientific way in which he explains what happens when ingredients such as eggs, sugar, and flour come together. If I look at the English-speaking countries, many are the authors that embrace the same scientific approach, as Kenji Lopez Alt, author of The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science, and of cooking techniques that have gone viral, such as his reverse sear for cooking steak.

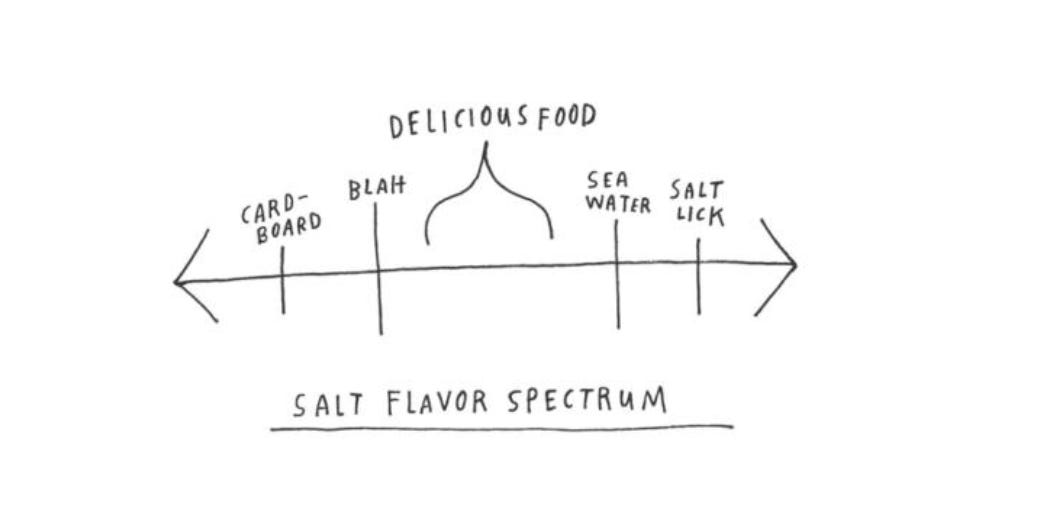

Then, there is Samin Nosrat, famous for her Netflix series Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, and especially for the book of the same name, published in 2017. According to Samin Nosrat, when we master these four elements of the equation—salt, fat, acid, and heat—we are able to cook consistently well. This is a book that has no pictures, but illustrations, diagrams, and schematisations, scientifically explaining how to make a salad dressing that balances acid and fat, or how the use of salt spans a spectrum that goes from cardboard, passes through blah, reaches delicious food when there is a balanced use of salt, and then continues on to seawater and salt lick.

A recipe is resistance, political activism, and cultural memory.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, two food writer friends from London—Olia Hercules, a Ukrainian, and Alissa Timoshkina, a Russian of Ukrainian descent—were petrified. A feeling shared by so many of us, even if not directly touched by the war as they were.

Within days they reacted by sharing what is most intimate, common, everyday: family recipes, and historical memory of a country. While Russia was trying to deny the cultural, political, linguistic, and even gastronomic identity of a country, they reaffirmed it by sharing the richness of Ukrainian cuisine, with borsh, fermented food, rich baked goods, and stuffed fresh pastas.

Despite my strong Ukrainian identity, I have always cherished and taken pride in the cultural diversity that we were so lucky to enjoy in Ukraine. My paternal grandmother is Siberian, my mother has Jewish and Bessarabian (Moldovan) roots, my father was born in Uzbekistan and we have Armenian relatives and Ossetian friends. - Olia Hercules, Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine & beyond

Their action quickly evolved from an online conversation to a global campaign and community of people, a movement that traced the footprint of the Cook for Syria project. Through collaboration with other British and European food writers, Cook for Ukraine was thus born, a project that quickly spread around the world. This project is based on sharing Ukrainian recipes, and the stories they bring with them, supper clubs and themed dinners, online and offline events, and charity bake sales. In one year they raised more than 2 million pounds for three humanitarian organisations: UNICEF, Choose Love, and Legacy of War.

Do you see the disruptive force that a recipe can have? It speaks on a visceral level, and it can often delineate the identity of a people, their typical products and customs, more than a historical essay.

But what happened with Ukrainian recipes has happened, in other ways, to us Italians as well.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, five million Italians emigrated to America, fleeing hunger and misery. They left behind severe conditions of poverty, and a country where they were still far from having a national cultural and gastronomic identity, let alone regional.

According to Alberto Grandi, professor of Economic History and Food History, and author of DOI, Denominazione di Origins Inventata, a brilliant book, and podcast, it was these immigrants, often frowned upon by the local communities into which they struggled to integrate, who built much of the tradition of Italian cuisine. In America, they found those products that they could only dream of in Italy. They created a cultural melting pot where Northern and Southern traditions met.

This new cuisine was then brought back to Italy with a second counter-exodus when emigrants returned to their homeland. Thus was born a conversation between two worlds that later led to the creation of what is now Italian cuisine.

And guess who played a central role in this creation of the Italian cultural and gastronomic tradition in America? A cookbook, what is now simply known as the Artusi, or La scienza in cucina e l'arte di mangiar bene, first published in Florence in 1891.

Artusi and his recipes would become for the Italian communities in North America a tool for literacy, cultural affirmation, gastronomic identity, and social redemption. The Dante Alighieri Society, whose aim was to preserve the use of the Italian language among emigrants, purchased several hundred copies of this manual.

We have seen that a recipe is a blend of poetry, science, and political activism. So what does it take, then, to write a recipe well?

Any well-written recipe will have at its core these three components, which will vary according to the type of recipe, the aim, the sensibility of the person writing and sharing that recipe, and his or her style. There is, however, one element that is always there, whatever approach is chosen to tell the recipe, generosity.

Generosity is needed. We need to take into account critical steps, possible mistakes, different techniques and skill levels, the ability to anticipate challenges, and the use of different ingredients. We need to remember that we are not writing a chronicle of what happened in our kitchen. We are writing a recipe for other people, in other kitchens, who will cook our recipe at some time in the future.

And to do that, it is necessary to be generous. Generous in the amount of detail provided, in sharing little tips, descriptions and explanations that can be applied to other recipes as well.

So don’t underestimate the strength of a strength. They can become a conversation and a story with an open end.

Now it's your turn. Have you ever thought about the world behind a recipe? When you read a recipe, what aspect is most important to you?

More links on recipes

Here you can read another article on recipe writing, from a few weeks ago, which elaborates on the concept of generosity.

Here you can read how failure is one of the components of my job. It makes me not only a better home cook, but also a better teacher and a better recipe writer, because now I recognize the pitfalls of a recipe, and I can explain how to defuse them.

Here I shared what guided me to select the more than 100 recipes that ended up in Cucina Povera. You can also find the bibliography of Cucina povera.

And don’t miss this article written by

, On Recipe Writing.

What a beautiful and thoughtful treatise. Thank you for sharing it with your readers.

I love this and how you describe the recipe in so much detail. I have always loved your blog for the stories behind the recipes and not just the recipes themselves. I collect cookbooks and especially love those that tell stories of family or country or culture that goes with the recipe. They transport me to their location with the story and with the food! Thank you for sharing! xoxo Lisa